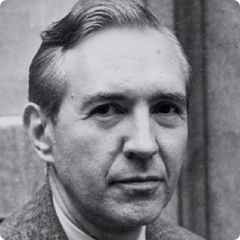

I get the sense that Jacques Barzun is one of those men on whom the label "men of letters" fits awkwardly, if at all. Like Henry Adams, his collected works merely allude to his literally unaccountable interests. Background: only child to French parents, who send him to America for his college education; teaching the Great Books course at Columbia University with Lionel Trilling; becoming the university's provost; literary advisor to Scribner's; winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The Internet has been good to generalists, but the medium's tendency towards atomization transforms any generalist into a specialist. What makes Barzun preferable to Adams is the refreshing way in which his diverse portfolio supports Orwellian clarity and directness. He doesn't write like an embittered insider banished to the periphery; rather, he proceeds like a scientist making deductions after studying data, no matter how unpleasant. Curiosity is his muse. Barzun embodies the spirit of nonplussed, enlightened humanism.

I get the sense that Jacques Barzun is one of those men on whom the label "men of letters" fits awkwardly, if at all. Like Henry Adams, his collected works merely allude to his literally unaccountable interests. Background: only child to French parents, who send him to America for his college education; teaching the Great Books course at Columbia University with Lionel Trilling; becoming the university's provost; literary advisor to Scribner's; winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The Internet has been good to generalists, but the medium's tendency towards atomization transforms any generalist into a specialist. What makes Barzun preferable to Adams is the refreshing way in which his diverse portfolio supports Orwellian clarity and directness. He doesn't write like an embittered insider banished to the periphery; rather, he proceeds like a scientist making deductions after studying data, no matter how unpleasant. Curiosity is his muse. Barzun embodies the spirit of nonplussed, enlightened humanism.The average reader knows Barzun's From Dawn to Decadence, a mammoth study of Western civilization that was a surprise best-seller in 2000. Uneven pace notwithstanding, it's a marvel, a model of elegance and sweep. Like his heroes Macaulay and Gibbon, Barzun treats history as fiction; characters are sketched at leisure; themes are developed in a lapidary manner, unfurled with the promise that they will be explained but not pinned down. In almost every sub-chapter Barzun dismisses orthodoxies; he's particularly incisive when assuring us that women did not do so badly as contemporary thought would have us believe:

There always have been hundreds of women in all ranks who were in fact rulers -- sometimes tyrants -- of their entourage, as well as hundreds of others who wrote, sang to their own accompaniment, or practiced one or another of the ornamental crafts. The notion that talent and personality in women were suppressed at all times during our half millennium except the last fifty years is an illusion. Nor were all women previously denied an education or opportunity for self-development. Wealth and position were prerequisite, to be sure, and they still tend to be. The truth is that matters of freedom can never be settled in all-or-none fashion and any judgment must be comparative.Can anyone read Barzun's excerpt and find fault with it? As attractive as Virginia Woolf's portrait of Judith Shakespeare is in A Room of One's Own -- a triumph of the novelist's art, let's remember -- the ease with which Woolf dismissed what can only be called the triumph of the will in creative personalities is startling. It's not that the strong survive; think of it as the holy compulsion to create, more powerful than our sentimentalities about repressed talent (think of Jane Austen scribbling quietly behind her needlework, ignoring patronizing remarks from her family). From Catherine de' Medici to Louise Labe (Barzun's story of this poet, musician, linguist, and soldier -- at sixteen! -- is one of his gems) to Christine de Pisan to Florence Nightingale, history records achievements by women as world-historic as any man's. From its discursive method to the assertiveness of Barzun's prose, FDTD is a quiet repudiation of the university's version of a Hegelian view of history: progress, Barzun implies, is a specious notion. If we're looking for historic examples of How Far We've Come, Barzun suggests we draw correspondences from oft-ignored socio-literary moments -- such as the frequency with which Edward FitzGerald's gelid, rather racy translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam appeared on Edwardian coffee tables.

Other subjects and personages re-evaluated: how slovenly Shakespeare could write (Barzun quietly notes the dull passages, terrible puns, "ludicrous images," and "insoluble syntax," all of which should make Harold Bloom weep); Diderot (always in Voltaire's shadow); the remarkable wit of Sydney Smith, a precursor to Oscar Wilde; the novels of George Meredith (I've put down The Egotist more than once in ten years); the once-immortal, now-neglected George Bernard Shaw, who emerges as one of Barzun's heroes. The final movement's descent into a rote condemnation of late twentieth century vulgarity isn't less excusable for being predictable, especially for one who scorns progress but never embraced Adams-esque theories about entropy. Actually, I give Barzun credit for sweetening his jeremiads with the kind of batshit inductive leaps I've always admired in great thinkers: he says that, no joke, young kids who join gangs fall prey to the temptations of...Satanism.

If From Dawn to Decadence seems too daunting, Perennial Classics recently published a splendid distillation of this centenarian's work. Despite his idiosyncrasies, he should be read -- cited -- more often.

3 comments:

"now-neglected George Bernard Shaw"

Neglected by who? He's one of my favorite writers, and I know plenty of people who read him!

Also, GBS, best music critic ever?

Very encouraging! Neglected by academe, then. And, yeah, Barzun has nice things to say about Shaw's music crit.

Shame. I was taught Shaw in two separate classes. Granted, my focus was English Lit., but yes, I need to read Barzun. Thanks for the tip!

Post a Comment