Sunday, December 30, 2007

She did it all for Hannah Montana

The most amusing -- and dreadful-- news story I've read in the last month.

Friday, December 28, 2007

A few movies

What I've seen:

What I've seen:The Savages: The writer-director of Slums of Beverly Hills can't resist a too-cute opening montage of seniors pirouetting a la Busby Berkley against a Barry Goldwater-approved Arizona backdrop; or giving Laura Linney a breakup scene with her boyfriend instigated by a question about her fern (it's one of those details designed to develop character of which Cameron Crowe is so fond, like the bit of business in Singles involving

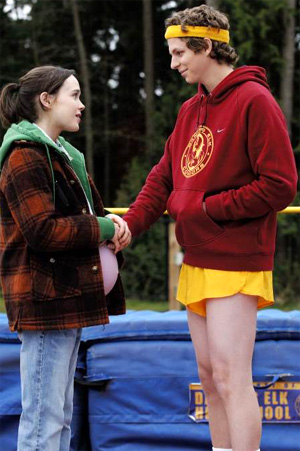

Juno: "Jason Bateman's character is one of the members of Vampire Weekend ten years later," I wrote somewhere today. Thank You For Smoking's Jason Reitman deepens his talent for exacting portraits of trends and mores skewed at least a half-dozen times in the thirty years since The Graduate. He's a selfless talent too; he honors the intentions of the material being adapted. The first hour is such a meticulous rendering of screenwriter Diablo Cody's hipster gotcha-every-few-seconds approach that I wanted to run into Love in the Time of Cholera, playing next door. It's "Papa Don't Preach" written by Lily Allen. Then Reitman-Cody take their feet off the gas pedal, and allow the natural empathy of actors like Alison Janney and Jennifer Garner (in a lovely, disarming performance that's one of the year's best and least acclaimed) to absorb Ellen Page's tuba blast of a performance. And knobby-kneed Michael Cera (who's got no scenes with "Arrested Development" costar Bateman) has gotten more mileage out of shades of befuddlement than any actor since Buster Keaton.

This is England: White riot, I wanna riot, white riot, I wanna riot of my own.

Tuesday, December 25, 2007

Monday, December 24, 2007

The only hint of discord on what's so far been a lovely vacation is learning that Tim Finney just had a benign tumor extracted. All news is very good, apparently, so we can all breathe a little easier.

I know Tim slightly from ILM, numerous private emails, and the R&B blog assembled by Andy Kellman (which, sadly, seems on sabbatical). His musings on pop and dance music combine the best common sense with un-self-conscious erudition; you sensed his brain humming as he listened. His affective formalism is at its best when he parses the evolution of a singer's emotional state over the course of a song, as he does here in this post about Jacques Lu Cont's Thin White Duke mix of the Killers' "Mr. Brightside" that's much the best thing ever written about it. I wooed him many times to write for Stylus -- his sensibilities and the magazine's would have been a perfect marriage -- but he gave me nothing but polite demurrals. Our discussion earlier this year on Fleetwood Mac's Mirage was an awful tease: I wish we'd done this sort of thing more often.

Maybe his best contributions this year were to this gargantuan thread which, beside fine postings from Al Shipley, Chuck Eddy, and Jess Harvell, is dominated intellectually by Tim in the last third.

Good luck, Tim. Happy holidays.

I know Tim slightly from ILM, numerous private emails, and the R&B blog assembled by Andy Kellman (which, sadly, seems on sabbatical). His musings on pop and dance music combine the best common sense with un-self-conscious erudition; you sensed his brain humming as he listened. His affective formalism is at its best when he parses the evolution of a singer's emotional state over the course of a song, as he does here in this post about Jacques Lu Cont's Thin White Duke mix of the Killers' "Mr. Brightside" that's much the best thing ever written about it. I wooed him many times to write for Stylus -- his sensibilities and the magazine's would have been a perfect marriage -- but he gave me nothing but polite demurrals. Our discussion earlier this year on Fleetwood Mac's Mirage was an awful tease: I wish we'd done this sort of thing more often.

Maybe his best contributions this year were to this gargantuan thread which, beside fine postings from Al Shipley, Chuck Eddy, and Jess Harvell, is dominated intellectually by Tim in the last third.

Good luck, Tim. Happy holidays.

Saturday, December 22, 2007

An addendum to my last post regarding ageing: bitching about "compressed" schedules, i.e. not enough time to listen to every album you want before year-end lists are due. I'll post the music lists before the end of the year, but, thanks to South Florida's erratic release schedule, will wait on movies, especially since I'm catching up on a few late arrivals (Juno, The Savages) over the holiday.

Thursday, December 20, 2007

Like a bad trip that won't go away, Ethan Hawke's teeth in Before the Devil Knows You're Dead haunt my sleep. Forcing his voice through those yellowed, sharp babies produces the best imitation of Tim Roth's shot-in-the-belly spams in Reservoir Dogs I've ever seen. It's indicative of the movie's anachronism that it reveres Hawke's hysterics as realism -- realism filtered through the Method. Kelly Masterson's script too. Hollywood's always been a sucker for comebacks, so it's some kind of achievement that an octogenarian like Sidney Lumet can spearhead a project as overwrought as The Hill, Prince of the City, and the worst parts of Network, among many, many others (Hollywood also respects a certain kind of aesthetic consistency, which is why Peter Weir still gets the occasional big assignment).

Like a bad trip that won't go away, Ethan Hawke's teeth in Before the Devil Knows You're Dead haunt my sleep. Forcing his voice through those yellowed, sharp babies produces the best imitation of Tim Roth's shot-in-the-belly spams in Reservoir Dogs I've ever seen. It's indicative of the movie's anachronism that it reveres Hawke's hysterics as realism -- realism filtered through the Method. Kelly Masterson's script too. Hollywood's always been a sucker for comebacks, so it's some kind of achievement that an octogenarian like Sidney Lumet can spearhead a project as overwrought as The Hill, Prince of the City, and the worst parts of Network, among many, many others (Hollywood also respects a certain kind of aesthetic consistency, which is why Peter Weir still gets the occasional big assignment).I'm relieved that, as the various critics groups circle the waters, this bit of awards chum has been comparatively overlooked. All I took away was Lumet's unexpected detachment from the scenes in which Philip Seymour Hoffman's skeeze visited a heroin dealer's expensive downtown loft; for a few minutes we're thrown into a Tsai Ming Liang film. Hoffman has never employed his bulk to a better effect as he navigates the familiar geography, taking off his watch, tie, and shirt for what we think is a gay tryst. The dealer, by the way, is played by Blaise Hunter, whose boredom serves as counterpoint to the rest of the cast's grandstanding (his response to Hoffman's confession that wife Marisa Tomei left him: "Bummer."). It's a sign of progress that Lumet shoots him in long shot, without calling attention to his Man Who Fell To Earth wedge haircut and kimono. Or maybe he was repulsed. It's hard to know when Lumet clearly prefers Albert Finney's rutting-bison nostril flaring in closeup.

Tuesday, December 18, 2007

...and speaking of Mary J. Blige, here's a review of Growing Pains.

Grow old with me

During a free moment yesterday afternoon in Raleigh this weekend I had a chance to read Slate's rockcrit year-end round table, comprised of Jody Rosen, Ann Powers, and Robert Christgau. Their opinions (boy, do they love Kala, Arcade Fire, LCD Soundsystem, and Lil Wayne, but so does most everyone else; glad to see Bob's suspicious of Iron & Wine; would love to meet Ann's 83-year-old mom) are immaterial. What remains beyond the self-plagiarizing and a couple of frankly weird self-congratulatory remarks about adding girl-pop to a year-end list (Rosen's homebases of Slate and EW are not Lost at Sea) are a handful of chewy ideas, expressed too windily for my taste, but, hey, this is supposed to simulate three old pros sitting around a table, right? Particularly:

During a free moment yesterday afternoon in Raleigh this weekend I had a chance to read Slate's rockcrit year-end round table, comprised of Jody Rosen, Ann Powers, and Robert Christgau. Their opinions (boy, do they love Kala, Arcade Fire, LCD Soundsystem, and Lil Wayne, but so does most everyone else; glad to see Bob's suspicious of Iron & Wine; would love to meet Ann's 83-year-old mom) are immaterial. What remains beyond the self-plagiarizing and a couple of frankly weird self-congratulatory remarks about adding girl-pop to a year-end list (Rosen's homebases of Slate and EW are not Lost at Sea) are a handful of chewy ideas, expressed too windily for my taste, but, hey, this is supposed to simulate three old pros sitting around a table, right? Particularly: It's fine for [Ann Powers] to like music I don't care for—she helps me understand its meaning for those it touches. The music opens them up, she opens me up. The reason all of us have such problems with indie orthodoxy—really orthodoxies, since, to cite just the two examples at hand, the Ryan Adams-Wilco-Josh Ritter Americanans are nowhere near hip enough for the half-assed revisionists and band-of-the-month snobs of Pitchfork and its many inferiors—is that we don't sense much emotional generosity there. The formal conservatism of the former and one-upping sectarianism of the latter—not to mention the rarity of engaging prose in either camp—seem stifling...Before we start thinking of new variations on the word "grouch," I should point out that the subtext of most of this round table's discussion is an acknowledgment of how age slows us down at the same time at which young people and technology speed past us. No, not an acknowledgment: an embrace, even. One of the odd things about my own maturation is how my ironic sense deepens at the same pace as my "emotional generosity"; it's too soon to know whether the former provokes the latter, but why not? At any rate, the usual strawmen that Christgau dismisses in the excerpt above are less onerous than other acts supported by my colleagues, like, say, Burial, whose constricted aesthetics and monochromatic appeal seem more representative. Ryan Adams and Wilco are at worst failed craftsmen; whether you prefer Battles depends on how much you accept craftsmenship as an end in itself, or think Battles are an act whose development bears close scrutiny.

Regardless, the fact that a lot of indie -- nomenclature growing increasingly meaningless with Rilo Kiley, the Shins, and Arcade Fire scoring high in Billboard's Top 40 -- horrifies me provokes no smug titters. Discussing music with good friend and colleague Josh Love this weekend, I admitted that as my self-assurance as a writer grows so does my fear of complacency. To be exiled to a tropical rain forest with neither guide nor map is no fun, and likely dangerous, but a thrill too. If it takes no great imaginative leap for me to accept heteronormative literature and music (it's a matter of course, actually), then wrestling with an Iron & Wine or Battles should be no different, and no less thrilling, results be damned. It's our responsibility as critics to assess art about which we know little and empathize less. I had the experience reviewing the new Mary J. Blige album; now there's an artist whose many rewards and unabashed pleasures (I've loved and feared her since 1994) still make me sick to the stomach when I'm compelled to listen to fifty-minutes-plus of her thumpety narcissism. If I risk a tone of bemused ambivalence, fuck it.

Thursday, December 13, 2007

Final essays to grade, reviews and proposals to write, and a weekend with friends in Charleston and Raleigh have made this a breathless week few days.

Having listened to roughly a third of my favorite albums of the year on the plane this morning (Jay-Z sounds great with Kingsley Amis!), I've realized that 2007 is 1987.

A moment of truth: reciting the lyrics to the songs on the back half of Robert Wyatt's Comicopera would likely get me tackled by TSA officials.

Having listened to roughly a third of my favorite albums of the year on the plane this morning (Jay-Z sounds great with Kingsley Amis!), I've realized that 2007 is 1987.

A moment of truth: reciting the lyrics to the songs on the back half of Robert Wyatt's Comicopera would likely get me tackled by TSA officials.

Tuesday, December 11, 2007

After two massive singles still getting lots of airplay on WHYI Miami, Timbaland featuring OneRepublic's "Apologize" has really hit the spot. No surprise: the track is a dead ringer for an Enrique Iglesias ballad circa 2002. And I love it...because it's a dead ringer for an Enrique song, albeit with a stronger rhythmic foundation. The guy knows how to keen too; when he glides over vowels in the chorus, I swear I could be his hero, baby. All my friends know how I resent the phrase "guilty pleasure," but...

Monday, December 10, 2007

I guess I'm a very bad homosexual for thinking that, with a few exceptional performances-- obvious ones at that -- I don't understand Edith Piaf. But I know why filmmakers do: she's the kind of subject of which award-worthy biopics are made, the more overwrought the better. Baffling and rhythmless, Olivier Dahan's La Vie En Rose rests snugly in the Walk The Line-Ray-The Doors tradition, except for the distributor's curious decision to release the film so early in the year ahead of the rest of the award bait; maybe they knew something we didn't, which is that, as usual, the Academy of Farts and Biases will assemble another disgraceful list of female Best Actress candidates as a reminder that they only consider sagging jugs after Labor Day.

I guess I'm a very bad homosexual for thinking that, with a few exceptional performances-- obvious ones at that -- I don't understand Edith Piaf. But I know why filmmakers do: she's the kind of subject of which award-worthy biopics are made, the more overwrought the better. Baffling and rhythmless, Olivier Dahan's La Vie En Rose rests snugly in the Walk The Line-Ray-The Doors tradition, except for the distributor's curious decision to release the film so early in the year ahead of the rest of the award bait; maybe they knew something we didn't, which is that, as usual, the Academy of Farts and Biases will assemble another disgraceful list of female Best Actress candidates as a reminder that they only consider sagging jugs after Labor Day.This is not to detract from Marie Cotillard's commitment. Gifted with a cutting delivery and an eloquent smear of a mouth that switches from defiant to opaque depending on the company (and the liquor; the mouth is swollen with pique after champagne), Cotillard embraces Dahan's conception of Piaf as the sum total of her awful childhood experiences: insultingly reductive, true, but at least Cotillard is honest. She reminds me of Faye Dunaway in Mommie Dearest: oblivious to the pillars crumbling around and on top of her, she sawed away like Caligula. The forgotten Susan Hayward also comes to mind. If this was still the fifties, Hayward (whose career peaked while playing these Kabuki-masochistic roles) would have played Piaf, with that showbiz lady distance between herself and the role that the Method, curiously, emphasized all the more. Dahan is so devoted to his tawdry vision of Piaf as Our Lady of Sorrows that no inductive leap escapes him. To wit: we're treated to the heroine going blind, recovering her sight, and losing her childhood guardian in the span of fifteen minutes. Thelma Ritter in All About Eve: "Gee, what a story. Everything but the bloodhounds yappin' at her rear end."

Plus, as an old woman she looks like Quentin Crisp.

An addendum to Saturday's post about Elizabeth Hardwick: a lovely obit by Jim Lewis. He's right ("Her great theme...was the way fictional characters inhabit a field of responsibility and act out the subtleties of their situations as moral agents in a bounded universe") and wrong (Hardwick was supple and rigorous, but to call her "the best literary essayist of the last century. Better—yes—than Edmund Wilson, better than Trilling or Steiner or Sontag" is hagiography, not serious criticism).

Saturday, December 8, 2007

Elizabeth Hardwick, R.I.P.

A couple of days old, but worth mentioning. As the one critic whose stylistic temperance was like distilled Essence De New York Review of Books, she was tart, civilized, and judicious -- a lot closer to Edmund Wilson and Lionel Trilling than Diana Triling (the little-read Mary McCarthy is another matter) . I don't know much about her work beyond the worthwhile Sight Readings: American Fiction; if you find a copy cheap (and you will), snap it up.

Thursday, December 6, 2007

Wednesday, December 5, 2007

It's a celebration, bitches

I'm baffled by complaints about Kanye's "ego problem," especially when as indentured servant to noted humble scion Sean Carter his productions swelled the latter's conception of himself like buttresses in a cathedral. Maybe people mean that Kanye's flow isn't good enough, which is to say that at worst his inadequacies render his contorted confessions as monstrously messianic as Bono's. A man who pens a couplet like, "Big Brother saw me at the bottom of the totem/Now I'm on the top and every body on the scrotum" has issues that Lance Bass is too boring to address.

I'm baffled by complaints about Kanye's "ego problem," especially when as indentured servant to noted humble scion Sean Carter his productions swelled the latter's conception of himself like buttresses in a cathedral. Maybe people mean that Kanye's flow isn't good enough, which is to say that at worst his inadequacies render his contorted confessions as monstrously messianic as Bono's. A man who pens a couplet like, "Big Brother saw me at the bottom of the totem/Now I'm on the top and every body on the scrotum" has issues that Lance Bass is too boring to address. His architecture stable and familiar enough thanks to the return of stable, familiar builders like Just Blaze and Kanye, the firm of Sean Carter can take immense satisfaction in promoting American Gangster. I get off on how great it sounds -- on an sonic level this is akin to a Pixar entertainment. When I'm paying so much for mainstream entertainment, I demand the deluxe treatment. As a back-to-basics move it's closer to The Blueprint than Reasonable Doubt, the latter of which bears the same relationship to Jay-Z's work as Run DMC does to Raising Hell: musicians often mistake spareness with "timelessness" (think of the retired "Unplugged" canard), and are therefore apt to overrate work made in comparative poverty whose aspirations can't match the results. The ominous, churning "Pray" hooked me from its first notes, and it allows Beyonce her most frightening vocal since "Bootylicious," which is to say she (and Jay-Z) don't project yearning so much as demand your abject worship. As a declaration of genius, "No Hook" is gentler and hence humbler than The Black Album's psychobabble-courting "Moment of Clarity"; if I were Ludacris, I wouldn't feel insulted. Think of it this way: if Bryan Ferry pulls me into a foyer and, haltingly, sadly, reminds me that white socks are, erm, not appropriate, old chap, at dinner parties, I'd remember the unease borne of good manners, not the fashion advice.

Even the album title's self-parody induces no groans, as it might have (and should have, maybe) in 2003. Context is all, and Jay-Z knows enough about how albums work to understand that craftsmen, like the veterans they are, no longer stumble into moments; they coordinate them after feeling the pulse of the populace. Fortunately, Jay-Z's also enough of a popular artist to realize that craftsmen must position the showroom lights in different places to create the illusion of novelty. A friend called American Gangster "Jay-Z's Some Girls." It's closer to Tattoo You, whose creators divided into fast ones-on-the-A-slow-ones-on-the-B and included a couple of sops to friendship and humility, two virtues plenty available in their older work if you were listening hard enough. Christgau's begrudging praise of the Stones album may as well be aimed at American Gangster: "But where The Blueprint had impact as a Jay-Z record, a major statement by an entrepeneur with something to state, the satisfactions here are stylistic -- beats, flow, momentum. And the artist isn't getting any less mean-spirited as he pushes forty."

Even the album title's self-parody induces no groans, as it might have (and should have, maybe) in 2003. Context is all, and Jay-Z knows enough about how albums work to understand that craftsmen, like the veterans they are, no longer stumble into moments; they coordinate them after feeling the pulse of the populace. Fortunately, Jay-Z's also enough of a popular artist to realize that craftsmen must position the showroom lights in different places to create the illusion of novelty. A friend called American Gangster "Jay-Z's Some Girls." It's closer to Tattoo You, whose creators divided into fast ones-on-the-A-slow-ones-on-the-B and included a couple of sops to friendship and humility, two virtues plenty available in their older work if you were listening hard enough. Christgau's begrudging praise of the Stones album may as well be aimed at American Gangster: "But where The Blueprint had impact as a Jay-Z record, a major statement by an entrepeneur with something to state, the satisfactions here are stylistic -- beats, flow, momentum. And the artist isn't getting any less mean-spirited as he pushes forty."

Tuesday, December 4, 2007

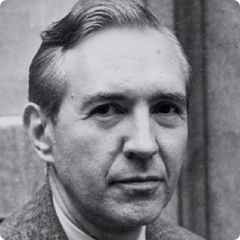

I get the sense that Jacques Barzun is one of those men on whom the label "men of letters" fits awkwardly, if at all. Like Henry Adams, his collected works merely allude to his literally unaccountable interests. Background: only child to French parents, who send him to America for his college education; teaching the Great Books course at Columbia University with Lionel Trilling; becoming the university's provost; literary advisor to Scribner's; winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The Internet has been good to generalists, but the medium's tendency towards atomization transforms any generalist into a specialist. What makes Barzun preferable to Adams is the refreshing way in which his diverse portfolio supports Orwellian clarity and directness. He doesn't write like an embittered insider banished to the periphery; rather, he proceeds like a scientist making deductions after studying data, no matter how unpleasant. Curiosity is his muse. Barzun embodies the spirit of nonplussed, enlightened humanism.

I get the sense that Jacques Barzun is one of those men on whom the label "men of letters" fits awkwardly, if at all. Like Henry Adams, his collected works merely allude to his literally unaccountable interests. Background: only child to French parents, who send him to America for his college education; teaching the Great Books course at Columbia University with Lionel Trilling; becoming the university's provost; literary advisor to Scribner's; winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The Internet has been good to generalists, but the medium's tendency towards atomization transforms any generalist into a specialist. What makes Barzun preferable to Adams is the refreshing way in which his diverse portfolio supports Orwellian clarity and directness. He doesn't write like an embittered insider banished to the periphery; rather, he proceeds like a scientist making deductions after studying data, no matter how unpleasant. Curiosity is his muse. Barzun embodies the spirit of nonplussed, enlightened humanism.The average reader knows Barzun's From Dawn to Decadence, a mammoth study of Western civilization that was a surprise best-seller in 2000. Uneven pace notwithstanding, it's a marvel, a model of elegance and sweep. Like his heroes Macaulay and Gibbon, Barzun treats history as fiction; characters are sketched at leisure; themes are developed in a lapidary manner, unfurled with the promise that they will be explained but not pinned down. In almost every sub-chapter Barzun dismisses orthodoxies; he's particularly incisive when assuring us that women did not do so badly as contemporary thought would have us believe:

There always have been hundreds of women in all ranks who were in fact rulers -- sometimes tyrants -- of their entourage, as well as hundreds of others who wrote, sang to their own accompaniment, or practiced one or another of the ornamental crafts. The notion that talent and personality in women were suppressed at all times during our half millennium except the last fifty years is an illusion. Nor were all women previously denied an education or opportunity for self-development. Wealth and position were prerequisite, to be sure, and they still tend to be. The truth is that matters of freedom can never be settled in all-or-none fashion and any judgment must be comparative.Can anyone read Barzun's excerpt and find fault with it? As attractive as Virginia Woolf's portrait of Judith Shakespeare is in A Room of One's Own -- a triumph of the novelist's art, let's remember -- the ease with which Woolf dismissed what can only be called the triumph of the will in creative personalities is startling. It's not that the strong survive; think of it as the holy compulsion to create, more powerful than our sentimentalities about repressed talent (think of Jane Austen scribbling quietly behind her needlework, ignoring patronizing remarks from her family). From Catherine de' Medici to Louise Labe (Barzun's story of this poet, musician, linguist, and soldier -- at sixteen! -- is one of his gems) to Christine de Pisan to Florence Nightingale, history records achievements by women as world-historic as any man's. From its discursive method to the assertiveness of Barzun's prose, FDTD is a quiet repudiation of the university's version of a Hegelian view of history: progress, Barzun implies, is a specious notion. If we're looking for historic examples of How Far We've Come, Barzun suggests we draw correspondences from oft-ignored socio-literary moments -- such as the frequency with which Edward FitzGerald's gelid, rather racy translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam appeared on Edwardian coffee tables.

Other subjects and personages re-evaluated: how slovenly Shakespeare could write (Barzun quietly notes the dull passages, terrible puns, "ludicrous images," and "insoluble syntax," all of which should make Harold Bloom weep); Diderot (always in Voltaire's shadow); the remarkable wit of Sydney Smith, a precursor to Oscar Wilde; the novels of George Meredith (I've put down The Egotist more than once in ten years); the once-immortal, now-neglected George Bernard Shaw, who emerges as one of Barzun's heroes. The final movement's descent into a rote condemnation of late twentieth century vulgarity isn't less excusable for being predictable, especially for one who scorns progress but never embraced Adams-esque theories about entropy. Actually, I give Barzun credit for sweetening his jeremiads with the kind of batshit inductive leaps I've always admired in great thinkers: he says that, no joke, young kids who join gangs fall prey to the temptations of...Satanism.

If From Dawn to Decadence seems too daunting, Perennial Classics recently published a splendid distillation of this centenarian's work. Despite his idiosyncrasies, he should be read -- cited -- more often.

R.I.P. Pimp C

How awful. I know little about UGK (and slept on Underground Kingz), but the last bits of news indicated that the guys had finally gotten back to starting careers.

Sunday, December 2, 2007

Ah, Larry Craig...

It gets worse. Four men, on the record, come forward and admit they had sex or suggestive encounters with the Idaho senator in the last twenty-six years.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)